Preserved food has been integral to the expansion of empires, though sometimes the eaters push back.

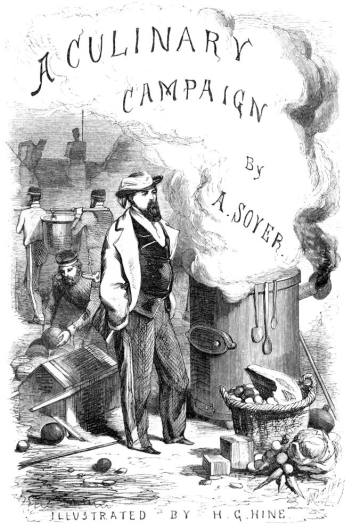

I’m writing a book about the politics of home canning. When I say politics, I mean the ways that home food preservation has been enmeshed in negotiations of power and influence, on scales large and small. This blog is a way for me to think through primary sources I’m encountering in my research—posters and labels and recipes and illustrations, like the frontispiece of a Crimean War memoir called Soyer’s Culinary Campaign (1857).

Let’s start large, at the Crystal Palace—the huge iron-framed glass building built in London’s Hyde Park for the Great Exhibition of 1851, just a few years before the Crimean War began. Officially, this mid-century international fair of mechanical triumphs was called the Exhibition of the Works of Industry to All Nations, and its main building housed nearly 8 miles of display tables covering a total floor area (on multiple stories) of about 23 acres. Full-grown trees sheltered comfortably inside its glass walls. The exhibition was a celebration of Empire: winning exhibitors received medals that featured Victoria and Albert on the front, and on the back a Latin phrase that means “For there is a certain country in the great world.”

Blood, Honey, and Vegetable Cakes

Among the nearly 14,000 exhibitors at the Crystal Palace—producers of pig iron, silk, cod liver oil, lichens, wallpaper, and every other imaginable creation—were those who entered products in Class H, “Animal Food and Preparations of Food As Industrial Products.” Judges in this category examined “portable soups,” “consolidated milk,” honey, blood (“and its preparations”), caviar, glues, gelatins, “articles of Eastern commerce” (such as shark fins and the “Nest of the Java Swallow”—a gauzy web of secretions apparently highly prized in China as an aphrodisiac), and, in Class H.1, “preserved alimentary substances.” Included here were tinned meats, bottled fruits and vegetables, and—taking home a Council Medal, the exhibition’s highest prize—M. E. Masson’s “dried and compressed vegetables,” manufactured by Chollet & Co. by means of dry heat and hydraulic pressure.[1]

I’ll get to tinned and bottled foods in future posts; for now, let’s focus on the big winner of Class H.1: dried vegetables. When Arthur Hill Hassall, a physician and pure-food crusader, tested a 4-inch-square of Masson-style vegetables a few years after the Great Exhibition, he noted that the cake’s fragmented and compacted state made it “difficult to determine what the nature of the vegetable was.” (He was looking at dehydrated cabbage, but it could also have been spinach, Brussels sprouts, beans, peas, sliced carrots, parsnips, potatoes, apples, endive, cauliflower, celery, or various herbs, all of which had been successfully processed in this way by Masson, a French horticulturist.)

Still, like the judges at the Crystal Palace, Hassall was a huge fan of these “dry and shrivelled” products. Once rehydrated, he noted, they tasted and looked better than vegetables preserved “in the moist way.” The fragments transformed in hot water, plumping, uncurling, becoming opaque, so that they resembled the fresh item’s taste, color, and overall appearance “in remarkable” and “really marvellous” ways.[2]

“What a Luxury for the Arctic Seas!”

One London paper of the period called them “mummy vegetables,” but this wasn’t a slur; the editors themselves, upon tasting a dish of green peas that had been two years dried, “found them as succulent and as palatable as if they had only just come from Covent Garden market.” When poured from the 3-inch-long rectangular tin box in which they were stored, the peas had appeared “about the density and digestibility of small [bird]shot,” but after 30 minutes of soaking they regained their shape and turned “a perfectly natural green.” In fact, when the tasters found that these patent vegetables retained both their natural “nutritive qualities” and their “vascular tissue,” they were moved to exclaim, “What a luxury for the Arctic Seas!” (Apparently a boon for Atlantic and Pacific voyages, too—the article was reprinted in a New Zealand paper in 1853.)[3]

Masson’s preservation strategy was in fact eagerly adopted by people and Powers that wanted to be out and about, beyond existing borders. The dried vegetable cakes weighed just 1/8 of comparable fresh produce and reportedly compressed 16,000 rations into one cubic yard. And they could withstand long voyages: in 1851, the year of the Great Exhibition, the French Navy affirmed that Masson-processed cabbage kept on board a man-o-war for four years in its desiccated state had been revived with “complete success”; 15 grams of the stuff were ordered for each sailor’s mess three times a week, alongside their salted meat.[4]

“It is impossible to over-estimate the importance of these preparations”

More than offering convenience or variety at home, then, these products made possible the conquest of previously autonomous spaces, and they sustained empire through commerce. As the jurors at the Crystal Palace acknowledged in their report,

“It is impossible to over-estimate the importance of these preparations. The invention of the process by which animal and vegetable food is preserved in a fresh and sweet state for an indefinite period has only been applied practically during the last twenty-five years, and is intimately connected with the annals of Arctic discovery.”

Demand for “preserved alimentary substances” had been created by 1) attempts to discover a northwest passage that would connect the Atlantic and Pacific Oceans, thus simplifying trade routes; 2) desires to “prosecute scientific research in [virtually] inaccessible regions” (such as the jungles of South America); and 3) aspirations to thrive in hot climates (“especially in India,” where scattered European families were often unable to consume quantities of freshly slaughtered meat before it spoiled).[5]

With improvements in sterilization and hermetic sealing during the first third of the nineteenth century, “the consumption of preserved meats became, at once, enormous. Hundreds of tons,” the judges wrote, “are annually transported to the East Indies and all our colonial possessions, and many are consumed by our fleets.” These processed provisions were thrifty: they reduced waste generated during food preparation, were lighter than whole animals (which inconveniently carried bones and skin with them on voyages), and limited potential decay to individual tins rather than letting putrefaction spread through entire casks of salted meat. Featherweight vegetables could nurse the sick aboard ship and prevent nutritional deficiencies. Then, too, the bounteous raw materials being harvested in the likes of Tasmania, Canada, and Australia could be efficiently processed and preserved abroad, then shipped back to England as cheap food for “the lower classes.”[6]

“Desecrated” Vegetables: Talking Back

Such effusive praise leaves me wondering about other voices, those who participated in these culinary campaigns from different perspectives. Did Madame Daniele St. Etienne, who also exhibited in Class H.1, find a market for her “specimens of vegeto-animal substances, meat, flour, &c. prepared for long voyages,” to be used in soups, puddings, pies, and other dishes? Though she received an honorable mention for a “bottle of dried and pulverised spinach,” the judges remarked that her “curious preparation resembl[ed] M. Masson’s, but the quantity exhibited is too small, and the general applicability of the process is not known.”[7]

And what about the soldiers, sailors, and other members of the “lower classes” who were treated to these industrial efficiencies? About a decade after the Great Exhibition, on Virginia battlefields during the US Civil War, John Davis Billings was less than ecstatic about dried veg. A private in the Army of the Potomac, Billings recalled in an 1888 memoir that Union soldiers were occasionally given a one-ounce, 2- to 3-inch cube of mixed “vegetables, which had been prepared, and apparently kiln-dried, as sanitary fodder for the soldiers,” a way to ward off scurvy. The cubes did swell to “amazing proportions,” he observed, and

“in this pulpy state a favorable opportunity was afforded to analyze its composition. It seemed to show, and I think really did show, layers of cabbage leaves and turnip tops stratified with layers of sliced carrots, turnips, parsnips, a bare suggestion of onions,—they were too valuable to waste in this compound,—and some other among known vegetable quantities, with a large residuum of insoluble and insolvable material which appeared to play the part of warp to the fabric, but which defied the powers of the analyst to give it a name.”

In one lot, inspectors found powdered glass between the vegetable layers, though Billings was unsure whether this was an act of Confederate sabotage or just “showed how little care was exercised in preparing this diet for the soldier.” His comrades—who felt the so-called desiccated vegetables were better fit for “Southern swine than Northern soldiers”—called “this preparation of husks” “desecrated vegetables.”[8]

Billings’s use of kiln-dried, fodder, stratified, residuum, insoluble, analyst, and even possibly his weaving metaphor (“play the part of warp to the fabric”) reveal his awareness of the soldier’s place within military-industrial-scientific complexes. Yet his wordplay (desecrated vegetables, Southern swine; the parallelisms of Southern swine/Northern soldiers) works to humanize and critique these circumstances. Instrumental as military campaigns were for expanding states and industries, they and the food technologies that enabled them were not received in silence.

[1] Exhibition of the Works of Industry to All Nations, 1851: Reports by the Juries on the Subjects in the Thirty Classes Into Which the Exhibition Was Divided, vol. 1 (London: W. Clowes and Sons, 1852).

[2] Arthur Hill Hassall, Food and Its Adulterations (London: Longman, Brown, Green, and Longmans, 1855), 431, 436.

[3] “Masson’s Patent Dried And Compressed Vegetables,” Lyttelton Times, April 23, 1853.

[4] Hassall 1855, 431-32.

[5] Exhibition, 1852, 154.

[6] ibid., 1852, 154-155. It should be noted that in 1852, the very year that the juries published awards for meat prepared by “Goldner’s process” (156), the eponymous Goldner (whose prices undercut other contractors) was apparently responsible for a tinned meat scandal that resulted in tens, and possibly hundreds, of thousands of pounds of rotten meat being discarded; read the gory details here.

[7] ibid., 1852, 156; Official Descriptive and Illustrated Catalogue of the Great Exhibition of the Works of Industry of All Nations, 1851, Part 1 (London: W. Clowes and Sons), 194. According to the building plan published in the Catalogue, the “Vegetable and Animal Substances Used as Food” display was in the South Gallery, with “Raw Produce” on one side and “Chemicals” on the other; across the aisle were ribbons, lace, and precious metals.

[8] John Davis Billings, Hardtack and Coffee, the Unwritten Story of Army Life, (Chicago: R. R. Donnelley, 1960), 141-42. Emphasis in the original.

I really am enjoying this website. The images and the information are both engaging.